The Rise of China. South-East Asian perspective.

The Rise of China and the regional challenges it poses. South-East Asian perspective.

The rise of China is a term referring to the unprecedented economic growth China embarked on since the introduction of the economic reforms in 1978. In an effort to stimulate the devastated through the Cultural Revolution, Great Leap Forward civil and Japanese war and a century of subjugation economy, China partially freed its state-controlled system. The central government encouraged relaxed state control prices, liberalised foreign trade and investment, formation of rural enterprises and private businesses. The opening-up initially led China to become ‘the cheap factory of the world’ later to be elevated to a position of the global leader in hi-tech. With a few ups and downs for over three decades, China saw an average growth rate of more than 9 per cent.

The origins of the term – Rise of China

The term ‘Rise of China’ has gained popularity as the unparalleled economic advancements were followed with the political, military and strategic transformation of the PRC, as China became more vocal about its strategic ambitions. This opinionated term assumes that the rise of China will inevitably lead to rising tension between Beijing and all those who may not benefit from China’s rise. The theory behind this term anticipates that the economic growth in combination with an unequal share of the pie in the international regime, regional security challenges and a drive to unify all parts of the country will push China towards a more assertive stance, which in its ultimate phase is inherently intertwined with the military expansionism. Thus, the propagators of the ‘Rise of China’ theory do not identify a scenario, where this process can be a mutually beneficial, win-win arrangement. This term is often used by the people who oppose China’s contestation of the international regime, an autocratic form of government or a different set of moral values represented by the state and development mechanisms.

The rise of China is usually portrayed in the context of the geopolitical power struggle with the US and a gradual loss of American economic and military superiority over the Middle Kingdom in relative terms. The Sino-American competition is an essential component in understanding ‘China’s rise’; however, it is more of a consequence, rather than a cause of this phenomenon. In order to fully understand the matter, one should familiarise him-/herself with the rationale behind the rise of China. These incentives, motives, threats and ambitions which best explain China’s strategic behaviour are all embedded on a regional level. Due to geographical proximity, the SEA countries are not only the first entities to encounter the consequences of China’s rise, but are also the ones (consciously or not) responsible for China’s expansionism.

South-East Asian place in the discussion about the Rise of China

In the debate about the Rise of China, the SEA is marginalised and is usually only brought up as a side topic to the power struggle between the US and China for regional supremacy and interests. This is why in elaborating on the causes behind the rise of China and what regional security challenges it entails, this article will pay close attention to SEA states’ perspective. This article will discuss why China’s economic expansion and the ever-growing regional aspirations clash with the Southeast Asian (SEA) states’ raison d’être and why does the majority of the SEA states perceive China as a threat. SEA includes Mainland Southeast Asia, also known as the Indochinese Peninsula comprising Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Peninsular Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Maritime Southeast Asia, also known as the Malay Archipelago, Brunei, East Malaysia, East Timor, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Singapore.[1]

Let’s look at the pages of history and it will teach us a vital lesson

The emergence of China on the political landscape as a global power is by far the single most important event on the world power politics chessboard in recent decades. As the discussion about the rise of China is most commonly centred around the Sino-American relations, since China was subjugated or isolated for much of the 19th and 20th centuries, did not constitute a major power or the US had limited interests in the region the main focus of the discussion starts with Deng’s ascent to power.

By this analogy, when a debate on why many SEA nations consider China’s rise a threat to their survival emerges, it usually disregards historical animosities between China and SEA prior to 1978. According to many scholars, China’s metamorphosis since the late 70s has no parallel in the history of the world, given the scope of the phenomenon and the consequences for the global order it entails. However, it is key to understand that the global scale of China’s resonance has to be limited only to exactly these last four decades. Previously, China has not been considered a global leader, let only a real contender of the world order from a Western perspective. The position of China as a strong regional leader, however, is far from a precedent. This article is built around the premise that the threat emanating from the Rise of China towards SEA cannot be interpreted irrespectively of the longer historical relationship between China and SEA which influenced each other for millennia.

In Besson’s words (2015), the most recent rise of China ‘represents a return to a long-standing historical pattern’ of encroaching dominance over the region. The embodiment of the imperial era – the tributary system symbolised the manifestation of China’s power, with its unquestionable ascendancy in a number of domains such as the economy, military, and culture. Unlike in the West, despite a few episodical exceptions (for instance Zheng He’s expedition), Chinese culture did not stimulate forceful proselytization of foreign nations outside of its immediate surroundings. All those who did not willingly join the divine tributary system, with the Chinese empire at the centre, were considered barbarian and unworthy of establishing a relationship. Jones, Khoo and Smith (2013) underline that today ‘the SEA returns into the preordained, pre-colonial order, where the inheritors to the Mandate of Heaven, exercise themselves over the Nanyang (a Sinocentric term encompassing SEA nations) through a neo-tributary [order] imposed through bilateral trade and policy ties’.

South-East Asian drive for independence

Today, however, much more than in the past, China’s demonstrable hegemonic aspirations are regarded with a high level of anxiety and suspicion (Jones, Khoo, Smith, 2013). It is mostly due to the obsessive concern over the national sovereignty SEA states express. This irresistible impulse for independence derives from the historical baggage of the centuries-long subjugation, first under China, then through Western colonialism, Japanese occupation and to Western oppression again, overthrown in a series of bloody wars.

A strong sense of nationalism emerged also around the question of the ethnic Chinese, who in large numbers have been migrating to the SEA states. Huáqiáo (people of Chinese birth) and Huáyì (people of Chinese origin) living abroad constitute up to 75% of the population in some of the SEA states. Often, they also amassed great wealth, becoming the rich in the respective countries. That is already a significant reason to develop prejudice towards an ethnic group, but what generated the feeling of suspicion and tarnished credit of trust was Chinese governments recognising the potential of the ethnic Chinese living abroad and utilising their capital for political purposes.

First, the Qing government saw rich Huáqiáo /Huáyì as a source of investment and a bridge to overseas know-how. Later, in the period succeeding WWII and decolonisation processes, most of the newly established SEA states interpreted the adoption of revolutionary Communism by the biggest country in the region as a tremendous threat to their survival. The fear was mostly a consequence of the espoused by China strategy of multilevel relationships. This encompassed China recognising the official government of a country, simultaneously providing logistical and economic support for the political and ethnic groups aiming to overthrow this government (Shambaugh, 2006,).

This policy raised unprecedented regional suspicion, predominantly because it was introduced, straight after the implementation of the ‘Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence’. These guidelines governing relations between states encompassed mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, mutual non-aggression, non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. Paradoxically, China claims the principles have been upheld ever since it was proposed in the 1950s.[2]

It was, however, the period of the Cultural Revolution (CR) 1966-1976, which influenced today’s shape of the Sino-SEA relationships to the largest degree. At that time, China permanently shattered its potential for being considered a benevolent neighbour. Chinese Communist Party (CCP) attempted to export the revolution through influential and wealthy Huáqiáo /Huáyì. During the CR and the immediate years afterwards, SEA nations feared that the chaotic revolution would spread to their countries. In result of the Cultural Revolution China found itself in a state of a complete economic, cultural, ideological and political malaise. SEA states aimed to avoid China’s faith at all costs. In consequence, many states limited their ties with China to a minimum, which in turn resulted in many Sino – SEA relations reaching their nadir.

The wind of change

Deng Xiaoping taking over China standing on a precipice of collapse, realised that it had to reshape its strategy to first lift the country out of poverty and then to bring back its lost glory. The central premise of this new strategy was to shift the focus from politics to economics. The economic dimension was recognised as a remedy to all the challenges China faced. The key to understand China’s rise is to recognise that the ruling party’s fundamental goal is its survival. Ever since Deng, but even more so now, CCP’s political mandate has rested on the notion that China keeps its economic development pace.

Secondly, the administration realised that in order to achieve the necessary economic growth to lift the country out of the striking poverty, China had to restore and shape peaceful international cooperation conducive to further development.

Deng understood that due to the prior exporting revolution policy and the sensitive topic of the Chinese minority overseas, China had been labelled with a large dose of suspicion. In an attempt to reinstate the legitimacy of the discredited Chinese Communist Party, Deng Xiao Ping engaged with a myriad of policies, namely depoliticizing China’s hitherto ideologically driven foreign affairs and downplaying the revolutionary aspect of Chinese Communism.

China aimed to bring back the glory lost during the century of humiliation. However, it learned its lessons and realised its growth could generate tremendous fear and suspicion among China’s neighbours. That is why Deng’s administration inaugurated the ‘do not seek leadership’ (‘bu yao dang tou’) and ‘conceal one’s capacities and foster obscurity, while achieving something’ (‘tao guang yang hui, you sou zuo wei’) strategies. It involved keeping a low profile and self-restraint aimed to facilitate China’s reintegration with the international community, namely East Asia. This temporary strategy was to pave way for the development of the country (Shambaugh, 2005, p. 49) until Beijing was ready to publicly express its ambitions.

China’s Rise and Demand for resources

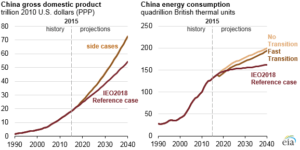

Deng Xiaoping’s strategic gospel, the emphasis placed on the economy and the espousal of a more peaceful, diplomatic approach laid solid foundations underneath China’s rise, quadrupling its growth between 1978-2000 (World factbook, CIA). In result of the state-led policies and the population’s efforts, as well as the encroaching globalisation playing in China’s favour, the rapid economic expansion of the world most populous country (1,444,883,717 in 2021) resulted in the enormously increased demand for raw materials, particularly energy resources (Cia, 2017). Rapid industrialisation and lifting millions of people out of poverty (including energy poverty) resulted in China becoming the world’s largest energy consumer (138.689 quadrillion Btu in 2017) and producer (110.23 quadrillion Btu in 2017) already in 2010 (EIA. U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2015). The forecast projects that China will consume two times more oil by 2027 than the total world usage in 2016 (World Bank, 2014), reaching 156 quadrillion Btu in 2035 (CNPC), However, China covers only 79% of its annual energy consumption needs. This energy imbalance serves as the key to understand the primary reason responsible for the whole chain of processes resulting in rising China being perceived as a threat on a regional and global scale.

Why South-East Asia interests China

How do the rise of China and the following demand for resources correspond with the perception of it as a threat by SEA? Bishop (p.617) argues that driven by the call for resources, which China could never fully obtain in sufficient amounts within its borders, to continue developing, China has always sought a remedy for its shortages in the nearest regions south to its borders. In order to further understand the threat China poses to SEA today, so to understand the roots of SEA’s fears and suspicion, it is crucial to understand how important is the place South East Asia occupies in China’s geopolitical strategy portfolio. The uninterrupted import of the resources (mostly energy) passing through the SEA, enables China a continuous economic growth, upon which the CCP built the ideological legitimization of its political mandate, effectively prolonging its reign. That is why under Deng, China acknowledged that it was a regional power with limited global interests (Shambaugh, 2005). Therefore, China’s regional strategy took priority over the (its alleged) global appetite (Shambaugh, 2005).

It is worth stressing that in result of China’s rise, SEA gained an economic growth stimulus for the whole region (Bartosiak, 2016) becoming a vital vain on the world trade map. On the other hand, the mutually benefiting economic cooperation leads to an ever-enmeshing net of interconnectedness. It is interpreted by realists as a leverage mechanism through which China exerts control over the region.

Therefore, the most conspicuous reason behind this region attracting China results from the combination of the economic development drive, geographical proximity and SEA’s growing importance and the richness of the resources it endows. Nowadays, the emphasis is placed on the rich in oil (even up to 11 billion barrels) and natural gas (about 190 trillion cubic feet) reservoirs as well as the shoal reserves (providing 10% of the world consumption) South China Sea (The U.S. Energy Information Agency) (Pacula, 2015).

Southeast Asia, has become home to an overwhelming majority of trade between North-East Asia, namely China’s imports and exports to and from Europe, the Middle East and Africa. On top of the energy sources, it is worth noting that, the foreign trade generates up to 35.7% of China’s GDP (2019), out of which over 70% passes through the SCS. Given the fear of a potential disruption of the imported resources or exported goods is linked with the vision of the survival of the PRC, the nature of the region is unquestionably granted the highest national security priority in China’s agenda.

An estimated 80% of global trade by volume and 70% by value is transported by sea. Of that volume, 60% of maritime trade passes through Asia, with the South China Sea carrying an estimated one-third of global shipping. With 5.3 trillion worth of goods transiting the South China Sea annually, generated through around forty-one thousand container ships passing the sea every year, it became home to over 21% of the world trade (Pacula, 2015).

South China Sea dispute

Due to the rapid economic elevation of the geostrategic importance of the region and the potential of SCS, many actors sought to annex the maritime territories within their borders, which ownership they claimed. The problem, however, emerged as some territories were claimed by more than one state. SCS, the main corpus delicti responsible for the generation of the regional tensions, encompasses over 2.24 million km² of contested territory (Pacula, 2015).

The origins of this dispute could be traced to the 1951 San Francisco Treaty, which after Japan’s relinquishment of the region, failed to stipulate the possession rights of the Spratly Islands, Paracel Islands, Pratas Islands, the Macclesfield Bank and the Scarborough Shoal (Jones, Khoo, Smith, 2013, p.107). The dispute intensified especially after the claimants (namely Taiwan, Vietnam and the Philippines) began to extract the resources from the contested territories.

Initially, China did not get involved in the scramble for SCS, due to the keeping low profile policy and the lack of technological and military capabilities to claim these territories. Nevertheless, the immediate geographical proximity of the SEA to China, located nearly at its doorstep, played an immense role in the shift of China’s policy towards the region. By recognising that its economic security is closely tied to the SCS, China adopted the 1992 Law of the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zones, whereby it laid claim to the entire SCS (Jones, Khoo and Smith, 2013, p. 108). This very unfortunate legitimization of such claims, basing on the historical possession of the territories dating back to the Xia dynasty, exacerbated the suspicion towards China, enflaming the lingering prejudices.

China’s more assertive rhetoric manifested itself first by the distraining of Mischief Reef in 1995 effectively joining the race over the SCS territories as the last out of six claimants (Dzurek, 1995). Contrary, to the actions taken by the other SEA states, China disregarded the dispute solving mechanisms adopted by ASEAN, an institution that effectively acts as the major contributor to the intraregional peace and security. The organisation’s reputation was only exacerbated by the inability to reconcile the historical claims with the ones based on the international law argumentation (Jones, Khoo, Smith, 2013).

Rise of China – a lethal threat to ASEAN’s unity?

By downplaying ASEAN’s territorial dispute-solving mechanisms, China poses tremendous challenge to the platform, but also to all of its members as it may lead to the organisation losing its meaning or (the already limited) enforcement capabilities. Beeson (2015) recognises that the rise of China presents the most severe challenge to the ASEAN’s perseverance. PRC revealed, numerous times, its propensity to assert its claims with more aggressive steps, what may eventually question the territorial integrity of some of the SEA states. Jones, Khoo and Smith (2013) add that the biggest problem of ASEAN is its inability to forge a common response to the threat posed by China’s rise. The core of the problem derives from the varying interests across the ASEAN states, with some recognising potential in China’s economic incentives, and the others being sceptical, emphasising dangers China’s rise heralds. The common response is necessary as individually the ASEAN states can present little leverage when confronting China. Striking a compromise, however, is highly unlikely to achieve due to the very divergent security priorities, deriving from particular geographical and historical circumstances, SEA countries are deeply rooted in (Beeson, 2015).

The inconsistency within the grouping increased after ASEAN expanded its membership to the continental SEA countries such as Laos or Cambodia, which brought the diametrically different perception of China to the ASEAN’s table. These two countries’ high reliance on China’s subsidies and trade (with China being the biggest trading partner), hence a more favourable position towards China serves as one of the fundamental obstacles in formulating a coherent ASEAN-wide answer to China’s actions in the SCS (Beeson, 2015).

China’s changing SEA policy

Another challenge, which ASEAN must face entails China’s stance towards SEA, which varies substantially over time from alarming to charming (Beeson, 2015). Due to the enormity of China’s rise relative to SEA states growth China has been at pains to assure ASEAN that, its rise is of a peaceful nature.

Various policies have been implemented in order to improve China’s image shattered during Mao’s era. Following the introduction of Deng’s policy, China gradually engaged with the international institutions, such as ASEAN. One of the most substantial changes in China’s SEA policy encompassed a temporary shift from the bilateral to the multilateral structure of the relationships. In the 1990s ASEAN attempted to enmesh China into the habits of good citizenship what resulted in the establishment of the ASEAN Regional Forum, the main multilateral mechanism with China (besides ASEAN +3), alluring China to engage with the non-confrontational and process-oriented approach. China’s more advanced engagement with the international regime, aiming to decrease the regional tensions was demonstrated by signing multiple agreements, such as the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of Seas (Jones, Khoo, Smith, 2013). A shift from norm avoiding to norm affirming behaviour, espoused in the “Charm offensive” strategy led to a tremendous trust-building rapprochement. In an attempt to further engage with the world, China inaugurated a strategy to share some of the burdens and responsibilities of a member of the international community.

It was particularly evident during the 1997 Asian crisis. China was prepared to bear substantial economic expenses to help ASEAN nations aiming to persuade them about the potential good resulting from China’s deeper involvement in the region, heralding the ‘golden decade’ (1998-2008) of China-SEA relations (Beeson, 2015). However, the time has shown, that China’s adoption of a non-confrontational ASEAN approach was not dictated by altruistic motives, but merely a cold calculation. At least this is the perception of the ‘golden decade’ by many spectators, who stressed that by partial adoption of ASEAN values China drew ASEAN into its sphere of interest and lulled ASEAN into a false sense of security.

At the same time, the already incoherent position of ASEAN was further undermined by the insufficient efforts of the US to maintain the organisation’s strength and reputation. Also, the resurfacing isolationist tendencies Washington espouses more eagerly with each term since G.W. Bush Jr. did not allow the US to increase its SEA military capabilities correspondingly to the military expenditure growth of China.

Since the II WW, the presence of the US provided security within this conflict-abundant region. The spectre of decrease of the American military presence vis-à-vis China (which happens to be one of China’s main national security goals) does not only pose a challenge to the regional stability by leaving SEA even more exposed to China’s assertiveness, but also raises concerns about the advent of the intra-regional tensions. (Beeson, 2015).

The relationship cannot be interpreted in a vacuum

It is crucial to mention that the modern-day relationship between China and ASEAN states did not emerge in a vacuum. Today, the context of the Sino-American relationship serves as the linchpin shaping the strategies of the PRC towards South-East Asia (Bartosiak, 2016). In result of the combination of historical processes and factors such as the economic prevalence, nearly unrestrained military capabilities, chain of regional alliances and agreements, the US controls the most strategic trade routes in the region such as Malacca and Singapore straits, which also happen to be arguably the most strategic maritime passages worldwide. American ability to project its power nearly at China’s doorstep has always been raising tremendous concerns within CCP, especially regarding energy supply disruption. However, during most of the Cold War, China lacked sufficient economic, political, diplomatic and military capabilities to question American presence in the region.

2008 unveils China’s true nature

For many decades, the growth in the political realm did not correspond symmetrically with the expansion of China’s economic might. The growing appetite for an elevation of its position within the international financial and diplomatic system pushed China to disengage from the once espoused low profile strategy (buyao dangtou), to a greater or lesser extent kept in place for nearly three decades (Shambaugh, 2005). Ever since acceding to World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001, China’s responsibilities started to grow, but the share of benefits has not been updated to China’s favour, remaining at a disproportionally low level.

Deng Xiaoping recognised the beginning of the dusk of the American empire and advised Chinese policymakers to wait for the optimal moment to seize the opportunity and take over the position of the world’s number one superpower and re-establish the world order. This policy added a caveat that CCP should only contest American hegemony when China’s core interests are at stake. President Xi Jinping recognised the time of the 2008-2009 crisis when most of the Western powers sunk in an economic malaise as a favourable environment for a change, finally letting go of the laying-low policy.

Military build-up

The most notable of the effects of this shift entails a tremendous growth in the military/defence budget spending. It amounted to $11.4 billion in 1989, $35.13 billion in 2003, $157.71 billion in 2012, $216.4 billion in 2016, growing up to $261.08 billion in 2019. The growth may have constituted an insignificant percentage of the GDP, i.e., 2.48%, 2.10%, 1.84%, 1.93%, 1.89% respectively (SIPRI) and it has decreased since 1989. However, as we look at the dynamics of China’s economy, we will notice that its growth potential outpaces the one of the western competitors.

Chinese defence budget may still be aeons away from the American one when we look at the absolute numbers of Beijing’s $261 billion compared to Washington’s $649 billion in 2019. However, except for a minuscule (0.1%) upswing in 2018 and 2019, ever since 2010 the US has been reducing the military expenses as a share of its GDP. Between 2011-2020 American spending decreased by 10%, whereas Chinese grew by 76%. The American economy is also expected to decelerate faster than the Chinese. With China being the only major power logging a positive growth in the covid-stricken 2020 environment, Nomura Holdings estimated China would surpass the American economy by 2030, whereas International Monetary Fund recalculated its forecasts and stated that with the appreciating RMB, the takeover would already take place in 2026. It means that if Washington does not rectify its policy, the military budget gap will be closing. It is also noteworthy that China tends to undervalue its military budget, whereas the US does the exact opposite by including as many semi-military costs into the military budget.

As a result of a continuously growing defence budget, Beijing’s ever-growing military capabilities represent the biggest challenge to the US and its SEA allies enmeshing the region in a spiral of security dilemmas. The uncertainty about China’s intentions intensifies with the transformation of the nature of the People’s Liberation Army from defensive to an increasingly more offensive character. It is best exemplified through the increase of the maritime power projection capability and a shift from the brown- and green- to blue-water naval capability, namely by the inclusion of the aircraft carriers.

On top of the six aircraft carriers China is expected to have by 2030, the demonstration of strength evinces a sophisticated plan of building islands through land reclamation within the 9-dash line (introduced already in 1949). Those SCS reefs or rocks transformed into islands are later equipped with sophisticated military machinery, facilitating China’s projection of power further from the mainland, enhancing its defence, offence and patrol capabilities. The policies introduced by China become more aggressive over time, with the assertion of numerous direct threats targeted at the other claimants, i.e., through a military intrusion into the Exclusive Economic Zone (Vietnam, Philippines and Taiwan), blockading ships, oil platforms, capturing of fishermen.

In Sino-American conflict SEA may be the biggest victim

In consequence of China’s muscle-flexing and dwindling trust in American help in event of a military conflict, the defence spending in the whole region increased by more than 50% in the last decade. Between 2008-2018 SEA was the fastest-growing military spending region in the world. The budgetary plans for 2015-2020 included some $60 billion dedicated to remilitarisation, predominantly the modernisation of the navy (Pacula, 2015). Except for Brunei, Malaysia and Timor-Leste, every country in the SEA has increased its conventional capabilities since 2009. Addressing China’s rapid growth of maritime power projection capabilities, SEA nations paid more attention to rapid deployment forces. Navies and the fourth-generation jet fighters tend to cover their lack of mine countermeasures, maritime surveillance, offshore patrol and anti-submarine capabilities.

Even though the proportion of military spending to each country’s GDP remained constant and still did not fit the definition of the arms race, the action-reaction pattern and low trust among the nations with lack of a regional dispute resolution mechanisms translate into a risk of misunderstanding in the future.

Power Transition

According to Mearsheimer and Kaplan (Besson, 2015, p.17), the assertion of power in the immediate surroundings of great powers is a natural behaviour of states, driven by pure calculation and rationality. The actions taken by China in recent years seem to fit well into the rhetoric of the realist school of thought foreshadowing an inevitable contestation of hegemonic power by a great power. The underlying theme in many realist scholars’ works, predominantly according to the power transition theorists, highlights that when one nation grows, it poses a threat to the leading power. In response, attempting to maintain its dominance the leading power will do everything to contain the growing adversary. Barack Obama’s “Pivot” to Asia-Pacific leaves no doubt that this strategy was formulated as a response to the rise of China in SEA. Many scholars believe that the contemporary skirmishes on SCS involving local actors serve as a prelude to the era of an overt Sino-US competition with SCS becoming a battlefield, where SEA nations would turn out the most disadvantaged, paying the highest price of all countries involved.

Conclusion

This essay demonstrates that the imperatives, the course and potential repercussions of China’s rise pose a tremendous threat to the security of South East-Asia in a number of domains. The conflict in the SCS demonstrates that the territorial integrity of multiple nations has been contested by China. The rise of China resulted in the increased demand for raw materials in China. SEA, as the region located in the most immediate proximity, endowed with substantial resources, became China’s one of the main national security objectives. Therefore, China altered its strategy towards the region accordingly. Initially, it was mostly involved closer cooperation with ASEAN in the 1990s and 2000s. The 2008 crisis diminishing the US’s unrestrained economic and military prevalence motivated China to pursue a more aggressive policy towards the region. The most recent political transitions and growing expansionism posed a threat to ASEAN, one of a few guarantees securing peace in the region.

The sense of nationalism across SEA states, to some extent built around the notion of anti-Chinese sentiments, has recently undergone a noticeable reinvigoration after China’s latest political shift evinced by the adoption of the more assertive strategies towards its neighbours. Even if the events building towards the lack of trust vis-à-vis China took place in the distant past, their repercussions impact the perception of China as a re-emerging superpower as a potential source of resurfacing danger today.

Being recognised as the chessboard between China and the US, the region serves as a forefront in the competition over the superiority in designating the world order, but at the same time infusing SEA with instability and lack of security.

[1] The Andaman and Nicobar Islands (India) are not referred to as a part of SEA in this article.

[2] https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjb_663304/zwjg_665342/zwbd_665378/t1179045.shtml

2 thoughts on “The Rise of China. South-East Asian perspective.”